There is a new sheriff in town. Global investors have been digesting the change in policy direction after President Trump’s return to the White House. In contrast to his first term, actions on the trade front have been a policy priority and the rules of the game are changing.

Within his first month back in office Trump has already announced 25% tariffs on goods imports from Mexico and Canada (subsequently delayed by one month); 10% tariffs on Chinese goods imports, in addition to the 25% tariff already in place on some goods; and a 25% tariff on all aluminium and steel imports. He has also directed his administration to draw up plans for reciprocal tariffs equivalent to those imposed by other countries on US goods.

Which countries might be in the firing line? How much does this matter for impacted economies, and what is the exposure for equity market investors?

Who is at risk of tariffs?

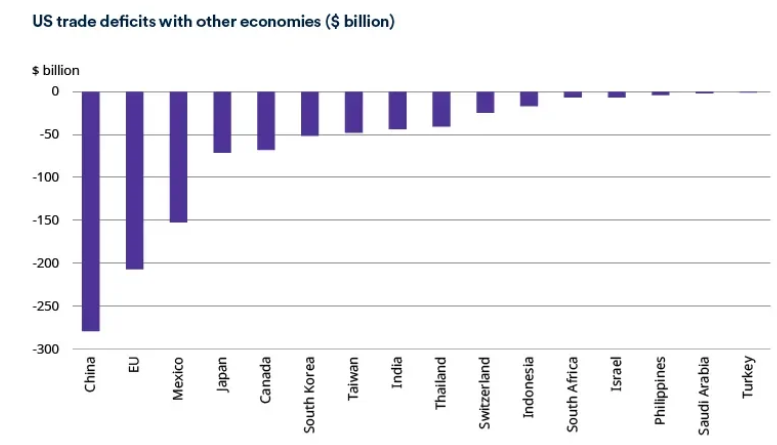

Trump has been unequivocal when it comes to trade, and his policy agenda prioritises tariffs as a tool to protect domestic industries and jobs. He has frequently cited trade imbalances as a key concern, both during his first term in office, and more recently. US trade deficits (where the value of imports exceeds exports) with partner countries therefore offer a proxy to gauge tariff risk.

Read more: Trump’s on-off tariffs: the potential effects in the US and elsewhere

As the chart below shows, China, the European Union (EU) and Mexico top the list of potential targets. This is not a revelation, with Mexico and China already the subject of executive orders on trade, and the EU now under scrutiny. However, there are other countries which could yet attract attention, including various Asian export economies. Trump agreed a revised free trade deal with South Korea in his first term, but several economies in the region have large deficits with the US.

Trade deficits are just one yardstick with which Trump may measure trading relationships. He has previously cited currency manipulation, unfair domestic subsidies, as well as intellectual property theft among potential catalysts for action. With reciprocal tariffs being readied, the average effective tariff rate is another metric to consider.

Do tariffs matter to these economies?

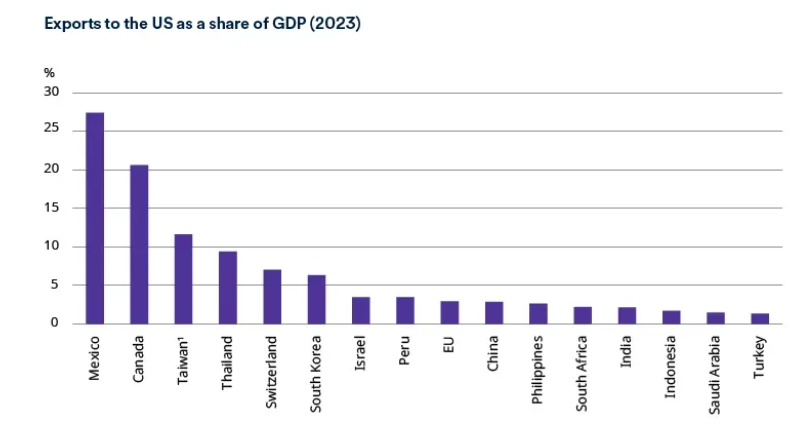

For those exporting to the US, the key question is what proportion of GDP do exports to the US represent; this captures the economic impact. Mexico and Canada are the most impacted on this measure. Asian exporters, Taiwan and Thailand also have a sizeable exposure.

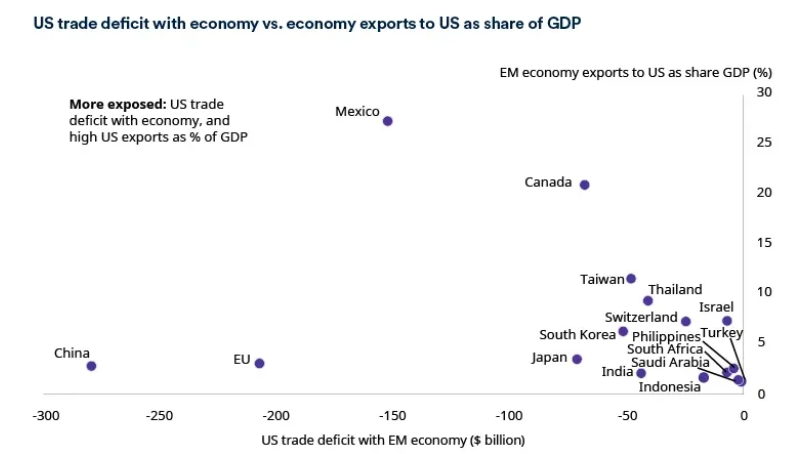

This next chart overlays the trade deficit – to proxy the risk of attracting US tariffs – with each economy’s exposure to the US via exports. Mexico is notably high, as is Canada. China is at high risk of attracting tariffs, as the US trade deficit and Trump’s previous actions illustrate, along with the EU. However, the economic exposure appears far lower than in Mexico and Canada. Whilst lower, this could understate China’s exposure to some degree, given re-routing of some goods that has taken place since Trump’s first trade war. Among the other markets which face a combination of tariff risk and economic exposure, various Asian exporters screen as vulnerable.

Which equity markets have the greatest exposure to the US?

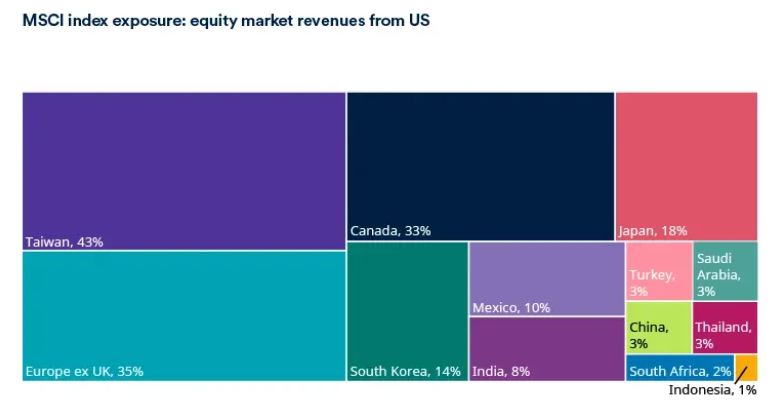

For equity market investors, gauging the individual market exposure to the US in revenue terms is equally important. What proportion of revenues could face a potentially negative impact from the imposition of tariffs?

This chart focusses on stock markets in economies which the US has a trade deficit with, as they are most likely to be in the firing line for tariffs. Other stock markets also have US exposure so face risks, even if economically they may be less of a focus, e.g. UK equities generate 27% of revenues from the US.

Taiwan stands head and shoulders above other markets on this basis. With 43% of revenues derived from the US. Microchips are the major export in question here, and Taiwan is the only leading-edge chip manufacturer in the world. As a result, you might anticipate that such a strategically important resource could be exempted or given some relief, though that is not guaranteed. Europe ex UK and Canada also stand out, as do various Asian exporter markets.

It is worth noting that the Mexican equity market, despite its heavier economic exposure, is less exposed revenue-wise, at least directly. China equity market revenues from the US are also relatively low at around 3%. However, this is not straightforward as these may not reflect complex global value chains. Domestic suppliers to export companies in these markets could face spillover effects. Meanwhile component manufacturers exporting to third countries for processing or final assembly before export onto the US could also be impacted.

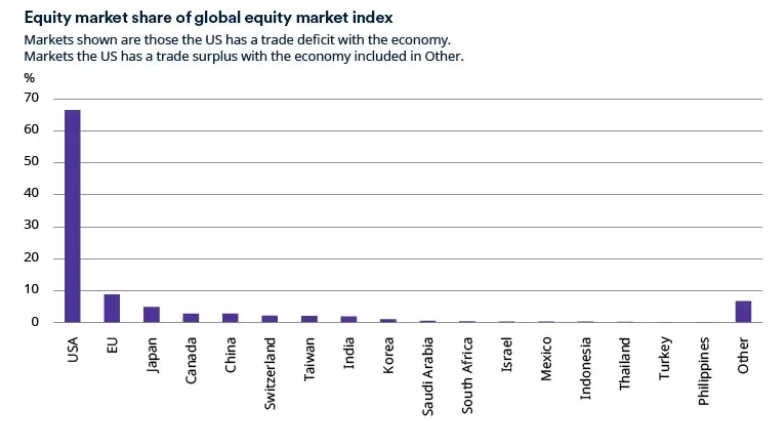

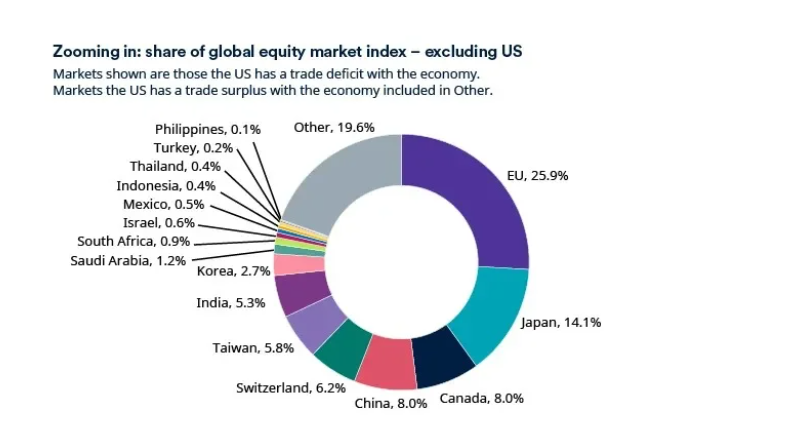

How does this reflect in terms of global equity market share?

For equity markets, the US is the dominant market in the MSCI All Country World Index, which includes both developed and emerging markets, with a share of 66% as at 31 January 2025. Equity markets of those economies with which the US has a trade deficit account for around 27% of the index. The EU is largest with a share of 9%, followed by Japan and Canada with 5% and 3% respectively.

To illustrate this more clearly, the second chart below shows the same data for the MSCI All Country World ex US Index. After the markets listed above, the next largest markets are China, Switzerland, Taiwan and India. The segment marked ‘other’ refers includes markets where the US does not have a trade deficit with economy, such as the UK (9%) and Australia (5%).

So far this year, the announced tariffs appear to have been milder than financial markets had anticipated. Against the backdrop of tariff rhetoric, global equities have advanced, including double-digit rallies in Europe and China, in US dollar terms, as at 19 February 2025. The potential for market volatility cannot be ignored, however, given risks of further tariffs, tariff rate escalation, and the prospect of retaliatory tariff or non-tariff measures.

Tariffs have potential to disrupt supply chains for both US and international listed companies. For companies in targeted economies, these could also suffer reduced competitiveness, or reduced market access. A potential for trade to be re-directed away from the US could lead to spillover effects for companies elsewhere in the world. The same could be argued for US companies if reciprocal measures are implemented. The ability of impacted companies to pass on the tariff impact to customers is a key factor. There may be some companies which are insulated from, or which can weather tariffs more than others.

If the US dollar strengthens versus the local currency in response to tariffs on partner economies, this represents a potential headwind for investor returns from partner markets in US dollar terms. The dollar is also relevant for US multinational companies with international revenues. It is worth bearing in mind that the S&P 500 revenue generation is only around 59% domestic. So US companies earn over 40% of their revenues from non-US markets. In addition to any currency translation impact, these companies could also be subject to any retaliatory tariffs or measures.

In summary, anticipating tariffs is complex, particularly given President Trump’s unpredictable approach. Some economies may stand out as at greater threat of tariffs, but understanding the risks and differences between economies, markets and individual company exposures remains crucial.

This article is issued by Cazenove Capital which is part of the Schroders Group and a trading name of Schroder & Co. Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.