Succession is the greatest test of any system, whether political, financial or familial. It protects achievements already completed, projects in motion and the personal careers of a regime. The risks of not planning correctly can be calamitous. But there can also be risks in laying out a succession. On the one hand, a successor can be a threat to the present leader, who can lose control if the process is not managed correctly. On the other, there is always the temptation for a current chieftain to undermine his or her successor. Yet the failure to plan can result in a sclerotic period of inertia under an obsolete leader, incapable due to age or illness from taking decisions, in which all the gains of a dynasty are lost. The structure of the succession is all important.

History offers many different prototypes. A key principle is that a succession should be agreed or at least understood by all players, or stakeholders as we now like to say. If there is not clarity, there can be a ruinous fight for spoils that destroys the legacy. Different societies have practised different methods of arranging this.

Firstborn or competition?

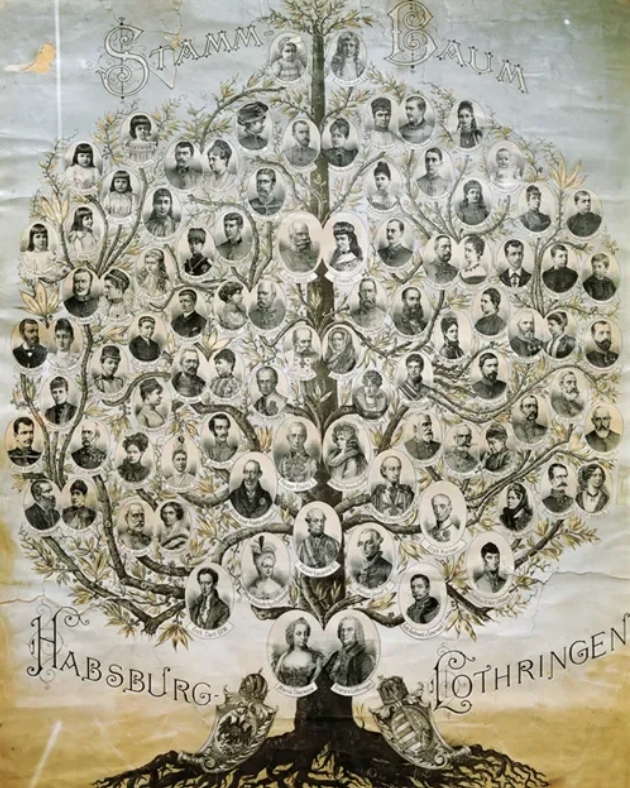

The monarchies of West Europe favoured primogeniture, succession of the eldest son, or if no son, then daughter. The advantage of this is that everyone knows where they are and who the successor is; there are no surprises, the team is already in place. Think of dynasties like the Habsburgs, or Bourbons and our own Hanoverians and Saxe-Coburgs. Even when an heir seemed feckless and self-indulgent, like Bertie Prince of Wales, the experience of waiting and being the heir meant that, as Edward VII, he became a very successful sovereign. The disadvantage is that the heir may be incapable, mediocre or rigid. See Charles I or Edward VIII.

The steppe monarchies – Turks, Mongols, Ottomans, Mughals – favoured a less structured succession, where various sons competed for leadership. The idea was that the fittest and ablest of the princes would destroy his rivals and the best ruler would emerge. The advantage? The toughest, most capable wins. This worked well in expanding, dynamic, aggressive polities like the early Ottomans or the early Ming dynasty in China. It meant, for example, that a ruler like Selim the Grim, Ottoman Sultan, could kill all his brothers and nephews, possibly even his father – but the system worked because he was by far the most capable of them all. After murdering his siblings, he went on to defeat the Mamluks and conquer the entire Arab Middle East in 1517, which his family ruled until 1918. It worked again when Selim was planning his own succession – he died young – but he ensured that the only son left alive was Suleiman, who was very able and became known to history as “the Magnificent”.

However, this approach, known as “Tomb or Throne” had a big flaw. There was a civil war every time there was a succession. In successful, expanding empires there were enough prizes and spoils to absorb the costs of civil war, but when the realm was stable or in decline, it could no longer take the shock. The danger then was that each succession battle risked destroying the very state the combatants were fighting for. This happened to the Ottomans, Mughals and many others.

Conservative Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd with supporters in his bid for the party leadership after the withdrawal of Margaret Thatcher from the House of Commons, London, November 1990. Left to right: Chris Patten, William Waldegrave, John Wakeham, Hurd, Virginia Bottomley, Tom King, unknown, Kenneth Clarke.

The dangers of clinging to power

Even in systems without families in control, succession plans need to be in place. Stalin toyed with many successors but always destroyed them before they succeeded him. He never groomed a capable successor – with significant consequences. The same can occur in a democratic context, with leaders like Margaret Thatcher.

It is a dilemma that may be preoccupying Vladimir Putin. The Russian elite is invested in the continuation of his stable dictatorship (if it can be called stable), but there comes a point when he will need to name an heir to reassure his henchmen. Yet that heir could quickly undermine and destroy him. If he moves first, the crisis could destroy the very system they are duelling to control. And so on. Whether a dictator or paterfamilias dividing up a family inheritance, the essential elements for success seem to be: a clear successor, a clear plan to divide the realm or estate amongst other heirs and a structure to deliver this.

Genghis Khan managed to achieve all this in a meeting with his feuding sons. He imposed his chosen heir, while dividing the leadership of the empire amongst them. He was a shrewd succession planner. Saddam Hussein, on the other hand, played family members off against one another – sons in-law vs. sons. However, he lacked an able heir while indulging his murderous, Caligularian sons without being able to make a decision for fear of surrendering control. The result was that he lost control of the succession and the family: his sons-in-law defected, then were lured home and murdered by his sons, who were themselves unsuitable as heirs. The lesson: be a Genghis or a Selim, not a Saddam or a Stalin.

Russian wooden nesting dolls, Matryoshka dolls, depicting (from L) Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin at a gift shop Moscow, July 2024.

This article is issued by Cazenove Capital which is part of the Schroders Group and a trading name of Schroder & Co. Limited, 1 London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU. Authorised by the Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority.